For 24 years, literary scholar Robert Alter has been working on a new translation of the Hebrew Bible and — “this may shock some of your listeners,” he warns — he’s been working on it by hand.

“I’m very particular — I write on narrow-lined paper and I have a Cross mechanical pencil,” he says.

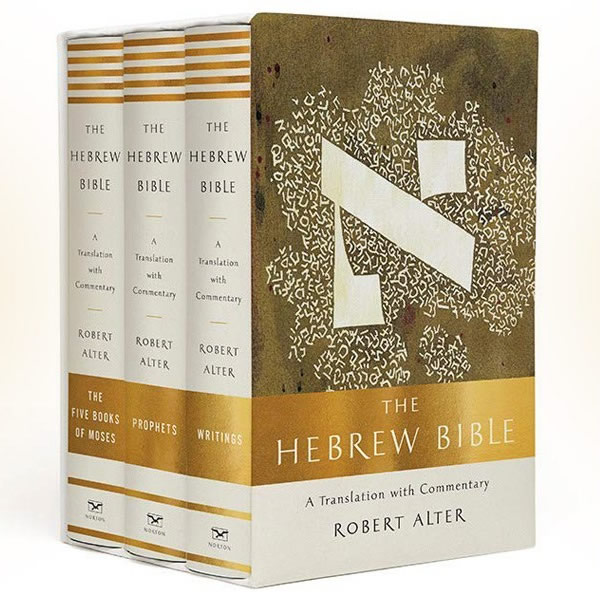

The result is a three-volume set — a translation with commentary — that runs over 3,000 pages.

Working solo for so long on a project of this magnitude can take its toll, he says: “If you keep going verse by verse, looking at the commentary and wrestling with difficult words and so forth, you can get a little batty.”

Alter says it was the “very high level of artistry” in the language of the Bible that drew him to the massive undertaking. “The existing English versions simply didn’t do justice to the literary beauty of the Hebrew,” he says.

As he worked, Alter found himself removing “Christological references” in the existing English translations.

“In trying to be faithful to the literary art of the Hebrew Bible I certainly edged it away from being merely a precursor to the New Testament — which is a different kind of writing all together,” he says.

Take, for example, the word “soul” — you won’t find it in Alter’s translation.

“That’s because the Hebrew word translated very often as ‘soul’ means something like ‘life breath,’ ” Alter explains. “It’s a very physical thing and there is no concept among the biblical writers in a split between body and soul. So I got rid of the soul.”

He also changed the wording in Psalm 23 — “thou anointest my head with oil,” is what you’ll find in the King James translation. “But the Hebrew verb does not mean ‘to anoint,’ ” Alter says. “The word that’s actually used by the psalmist means ‘to make luxuriant’ — something like that. It’s a very physical word. So after wrestling with other alternatives … I ended up saying ‘you moisten my head with oil.’ ”

Alter also tried to imitate the rhythm of the original — which was a challenge because Hebrew is a much more compact language than English.

“Words squeeze together,” Alter says. For example, in English it takes three words to say “he saw him.” But in Hebrew it takes just one. “You know it’s ‘he’ in the way the verb is conjugated, and then there’s a little suffix at the end of the verb that tells you it’s ‘him.’ ”

Alter also tried to steer clear of words with a lot of syllables — you don’t find many of those in biblical Hebrew, he says — and he omitted words that felt extraneous.

Alter points to one example in Psalm 30: The King James translation uses the phrase “What profit is there in my blood?” Alter removed “is there” to leave: “What profit in my blood?” Which he says is much closer to the rhythm of the Hebrew.

Alter always makes an audio recording of his work before handing it off to the transcriber — that way he hears everything out loud.

Of course, some day down the road another translator will come along and attempt to improve on his work.

“A translator of a great work is delusional if he or she thinks that there aren’t places where the translation falls down,” Alter says. He imagines this future translator will say: “That’s awkward. I can see he’s trying to get the literal sense of the Hebrew, but it sounds goofy in English and I can do better than that.”

Kevin Tidmarsh and Jerome Socolovsky produced and edited this interview for broadcast. Beth Novey adapted it for the Web.

via NPR

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.