by Paul Ford

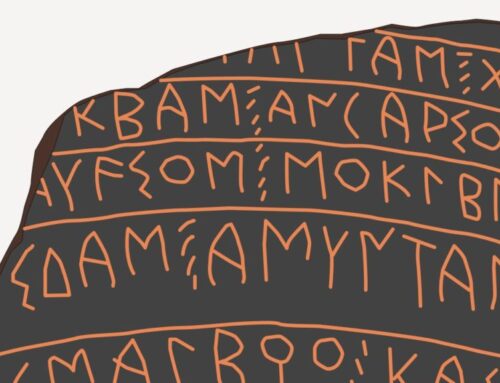

Image: Med Ness

Image: Med Ness

“The past is a foreign country,” novelist L. P. Hartley wrote. “They do things differently there.” He penned that in 1953, but in the digital era the past is now present and all around us: Millions of out-of-print books and historical videoclips, black-and-white movies, nearly forgotten TV shows and pop songs are all available with a credit card or in many cases for free. It used to be that, for economic and technological reasons, this cultural history was locked away. Libraries and corporate archives kept a small subset of it available, but the rest was in storage, out of reach. The reversal has happened in just the past decade. We are now living in a history glut; the Internet has muddled the line between past and present.

The transformation was slow at first, and hardly anyone besides librarians noticed. Project Gutenberg, founded in 1971, was a cheerfully radical effort to turn old books into text files. When the web came along, the Online Books Page appeared and began listing links to thousands of digitized titles. Then, after the turn of the millennium, the pace rapidly accelerated: Google set up Google Books, Amazon launched Kindle, and Archive.org started scanning public-domain works from libraries. Meanwhile, shifts in the economics of music, film, and video set off an explosion in the digitization of back catalogs, until then the furtive territory of file-sharing pirates. Spotify and Netflix, Apple and YouTube have all now built enormous businesses based on organizing the past for commercial exploitation. Suddenly we find ourselves living in an online realm where the old is just as easy to consume as the new. We’re approaching an odd sort of asymptote, as our past gets closer and closer to the present and the line separating our now from our then dissolves.

Six decades after Hartley wrote his famous line, the past is no longer a foreign land. Instead we’ve brought a weirdly literal truth to William Faulkner’s famously sphinxlike aphorism: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Take the Kennedy assassination, for instance. In honor of the event’s 50th anniversary last November, CBS streamed four straight days of its news broadcast from the period surrounding the killing so you could experience what it had been like in real time. Or consider this: World War II buffs can download radio broadcasts and listen to the rise of Hitler or the news from D-Day as you would have heard them back then.

More often, though, we don’t immerse ourselves in history; it’s just there whenever we want it, living right alongside the present. We can trace ideas backward in time, either by searching Google Books or (for a sum) through thousands of academic journals, using a few keywords to find sources that once were the sole domain of historians. Pick any historical subject and the Internet will bring it to life before your eyes. If you’re interested in vaudeville, you’ll find videos galore, while college football scholars can browse Penn State’s 1924 yearbook, complete with all the players’ names and positions. And every day, more history keeps washing up. Not long ago the news went out that a Philadelphia woman named Marion Stokes had recorded 140,000 VHS tapes of local and national news from 1977 to her death in 2012. Her collection has been acquired by the Internet Archive, and soon it will trickle onto the web.

This omnipresence of the past has weird effects on contemporary culture. Take any genre of music, from death metal to R&B to chillwave, and the cloud directs you not just to similar artists in the present but to deep wells of influence from the past. Yes, people still like new things. But the past gets as much preference as the present—Mozart, for example, has more than 100,000 followers on Spotify. In a history glut, the idea of fashionability in music erodes, because new songs sit on the same shelf as songs recorded five, 25, and 55 years ago, all of them waiting to be discovered. In this eternal present, everything can be made contemporary.

Perhaps the biggest result of the history glut is that managing all that history becomes the crucial act, both commercially and intellectually. Wikipedia is cataloging history, but to do so it needs to keep up an epic accounting of its own history—the billion-plus edits, each a record of human activity, that have built the encyclopedia over the years. Companies like Spotify and Netflix are mining the past as they host it, looking at their own enormous usage logs and analyzing that data to draw connections between types of people and types of music.

There’s an irony here: All of the data we’re collecting, all of the data points and metadata, is history itself. Much as we marvel at Babylonian clay tablets listing measures of grain, future generations will find just as much meaning in our log files as they will in the media we consume. Sure, Frank Sinatra sang a bunch of songs; sure, Jennifer Lawrence was a big star in 2014. But the log files tell you who listened, and when, and where they were on the planet. It’s these massive digital archives—and the records that show how we used them—that will be the defining historical objects of our era.

Source: Wired

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.